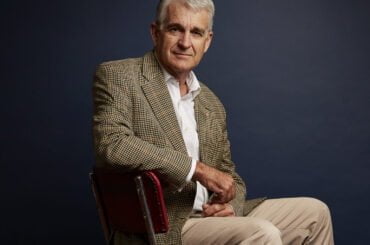

Conversations: With Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg, British Conservative Member of Parliament

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg hosts John Anderson in his home for this Conversation. They discuss the roots and future of conservatism, British politics and economics, the role of the West in global affairs such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the Chinese Communist Party, as well as diving into what motivates Jacob in politics.

Transcript ShowHide full transcript

Chapters

- Introduction

- Conservative Philosophy

- Conservatism and its relation to other ideologies

- Social Conservatism and why it's good for society

- Transgenderism

- Politics in the USA vs. other countries

- The current and future state of the Conservative Party

- Climate change, green energy, and net-zero

- Brexit

- The current state of the British Economy

- Britain's role as the mother-nation of modern freedoms

- The Monarchy

- Value systems in politics and families

- COVID and liberty

- The Chinese Communist Party

- The Russia-Ukraine conflict

- USA's future involvement on the global stage

- Growing disengagement in politics among youth

- What drives Jacob Rees-Mogg forward in politics

- Moral Relativism

- Conclusion

John Anderson: The right honorable Jacob Bruce MOG is the conservative member. [00:01:00] Parliament for Northeast Somerset in the west country of England, along with other senior political officers. He previously served as the leader of the House of Commons and the Lord President of the Council, the fourth of the great officers of state in the United Kingdom.

He’s the author of three books and he hosts State of the Nation on GB News.

John Anderson: Jacob, thank you so very much for your time here in London and your own home. It’s, it’s very good of you, indeed.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Oh, it’s a great pleasure. Thank you for coming. You’ve had a much longer journey.

John Anderson: Well, yes, it is a long way from Australia to Britain, but always worth the trip.

Conservative PhilosophyJohn Anderson: Now, it would be fair to say that you’re a conservative, both, I think by party affiliation and by, uh, Phil, uh, your own philosophical approach. Um, many would deride conservatism and do deride it today as a mere preservation of the status quo against change against progress. In your view, can you just give us a feel, [00:02:00] how would you describe the philosophy of conservatism and why you believe in it?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Yes. I think the idea that conservatism is just against change is wrong. I think what conservatism is about is first of all an understanding of human nature, and then the relationship of the individual to the state and how society is created and how through that you create the best, most successful, most prosperous society.

And part of that is constitutional, that we have learned that if you have a constitution that is based on freedom of speech, that rights of property, the rule of law and democracy, you become prosperous. If you look at all those prosperous countries in the world, they have those four aspects to their constitution and the people who seek to change that.

The radicals are ones who I think risk our prosperity. But you also want to look at the proportionality of the state. Does the state need to do it? Because. The state is built up from individuals, not the other way [00:03:00] round the family. Um, in terms of Leo 13th, in his encyclical, rum predates the state and therefore it has rights and freedoms that lead to the creation of the state.

And that seems to me to be a conservative underpinning of the policies that one then wants to implement as a politician.

Conservatism and its relation to other ideologiesJohn Anderson: Where do you think a conservative can find touchpoints in other political philosophies that they can constructively engage with and work with? And if you like respect?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I, I think there is an element of conservatism that touches with liberalism that if you take economics, the 19th century liberal economic prescription is one that is pretty attractive.

It ties in with allowing people to get on with their own lives, with understanding the primacy of individual liberty, and then applies it in an economic field. Which has gained the tag of economic liberalism. But I [00:04:00] think it’s not in any way, uh, in contradiction to conservatism. I know in my own

John Anderson: country, I found, uh, in my earlier days in the Parliament, that whilst I vehemently disagreed with their approach to the management of the economy and so forth, there were some of the old fashioned, if I can use that word, socialists in terms of their objectives.

You know, picking up the disadvantaged, the marginalized, and trying to ensure that they were part of Family Australia gave me a basis upon which I could at least talk and then discuss the reasons that I didn’t think their actual policies were the right way to achieve them, but there was something at a human level that we could communicate on.

Now, what I’m driving at is that that seems to be being washed out of the system. Now, unless you agree with me, and unless you’re aligned with my philosophy,

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think I agree with you on both parts that I, it was very noticeable. Last general election, the Red Wall in the UK that Boris managed to appeal to and get to vote conservative.

Why did they [00:05:00] vote conservative? Well, it wasn’t alignment of values, but they hadn’t changed their values so much as the Labor party had abandoned its values. So what? What did these people believe in? They were patriotic. They loved their country. Now, the Labor party in the UK historically had been a very patriotic.

Party. Jeremy Corbin wasn’t, he was very much an internationalist, very suspicious, uh, of patriotism. Um, he’d been in talks with the political wing of the RA in the 1980s. He’d been sympathetic to those hostile to the nation state, and that was rejected by labor voters. And I also agree with your point about wanting, um, to lift all boats, that the traditional socialist wanted people who were least well off to be better off.

Now they seem to be much more focused on what have become called woke issues on what you say and what you think. And if you disagree, you are a bad person. [00:06:00] And that’s a big change in, in politics. I, I wouldn’t say it’s yet infected the House of Commons, but in broader politics. And I think particularly for younger people, they do feel that if they express a view that isn’t fashionable, There are, um, deemed to be a bad person.

Social Conservatism and why it's good for societyJohn Anderson: If I can come to the term social conservatism.

Can I ask you how you would describe that and why you see it as good for society, particularly in the context of the, the line? I’ve always thought it was a bit of a home goal with people in the conservative country movement in this country saying we’re seen as the nasty party or the say, we’re seen that way.

You, you’ve allowed others to define you and you are owning it, it seems to me. But that’s an aside social conservatism and why it’s good for, for society.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I think it’s an important aside. I never thought that the Conservative party was the nasty party. I remember that speech made, um, by trees were made very well because the next day I was [00:07:00] speaking to a conservative group and it was, uh, in Shosha, the conservative women’s group.

And they had all these people who had worked for years for the conservative party. Who also did all the charitable work in their local communities, where they ran the village fate, all those sorts of things. And suddenly they’d been told they were nasty. So I thought it was wrong, foolish thing to say, um, and misunderstood what conservatism was about.

Again, back to my point on the family being the building block of society rather than the other way around, and therefore of the, of the state, the conservatives ought to support the family because it helps individuals in their lives. The success of people who are brought up in a stable family is statistically better than those who are not brought up in a stable family.

But, and the but is very important. It’s not for politicians to be judgemental on how others lead their lives, but it is for politicians to [00:08:00] allow people the freedom to lead their lives. What we have currently in the uk, and I dunno if this is also true in Australia, It’s a benefit in tax system that is actively hostile to the family.

You are worse off in a family than not in a family. This can’t be sensible. So I didn’t want to go back to a time where you stigmatize people living in other groupings or make their life more difficult, um, or, or make it harder for single parent families who have a pretty tough time for all sorts of reasons.

I don’t want to penalize or pilly them, but I do want to support the traditional family because I think it’s helpful for society overall.

John Anderson: Uh, and I suspect is is important in terms of economic outcomes ultimately.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I think that’s absolutely right. That, that if you, if you look at, um, success at school, if you look at the prison population, uh, and you correlate that with, um, children in care, I.[00:09:00]

Well, it’s a particularly difficult picture if you correlate it with broken homes altogether. It is a difficult picture. So the stability, uh, that you get from being in a traditional family is very helpful to people growing up and to their families. Uh, as I say, this doesn’t mean you want to criticize people whose lives haven’t worked out that way or have made other choices.

They must be free to do that, but you don’t want to have policies that actually make family life harder. We do seem

John Anderson: to be living in an age of, um, sort of quite radical self autonomy, you know, um, the idea that somehow the greatest virtue is that I am who I feel almost that I am. And that sometimes I think creates awkward dynamics, uh, in that that set of virtues is not particularly friendly to community, including family.

It can be a bit. A archaic a bit, [00:10:00] uh, you know, uh, anti organized government and, and, and stability, uh, and certainly anti-religion. So you’ve got a bit of a clash there with this modern idea, I think, of the virtue of self autonomy and what we’ve seen as the essential ingredients of a cohesive and cooperative

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: society.

Well, people can identify as they wish. They’re completely free to do it, but am I obliged to accept how they identify? It was in the papers recently that somebody had come to the United Kingdom from America and had identified as being British. Well, that doesn’t entitle him to a passport. A a and he may think he’s British.

Marvelous. I’m more in favor of people thinking that British great thing. But that doesn’t entitle you to the rights of a British citizen. It doesn’t give you a vote. It doesn’t give you a passport. It doesn’t give you a insurance number. And, uh, so I think people are [00:11:00] entitled to say what they wish it’s free country, but equally others are entitled not to change their behavior in accordance with somebody’s whim.

This has been the genius

John Anderson: I think, of western, uh, civilization over the last few hundred years. We’ve evolved to the point until it seems recently that we were able to accommodate one another’s deepest differences in a way that’s been quite unique. Uh, and one worries a little that it’s under attack.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Yes.

I, I mean, I think there is an intolerance. Um, and the intolerance mainly comes from the left, not from the right. Uh, I, I see this, uh, on, uh, I do a television program for GB News. I see this with some people that I interview. That people on the right who I disagree with, uh, don’t automatically think that I’m a bad person because of it.

Some people on the left just assume if you disagree, you must be bad. And the right very rarely feels [00:12:00] that towards the left. I agree. Intolerance is a bad thing. It’s bad for the cohesion of society, but it’s also a desperate arrogance because if you look at human history and you go back all through whatever records there are, we make terrible mistakes.

We all believe things which then turn out a hundred years later to have been wrong, unpleasant, false based on bad information, and therefore one ought to have a certain humility about one’s own views and certainties.

TransgenderismJohn Anderson: Talking of certainties, we’ve got a, you know, a very vigorous debate going on in all of our countries now about, uh, you know, the whole issue of transgender identity.

And, and I think you’ve been on record of saying that single sex spaces need protection. And we’ve seen some very ugly crashes over this in Australia, and we read of some terrible things happening happened in this country, frankly, where there have, there’s been a lack of protection, particularly for women in certain situations.

[00:13:00] Um, how do you think this debate, uh, might, might unfold? What, what would you say is the, from your perspective, is the right way to understand philosophically, transgenderism and the trans movement?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I, I think that the real issue is about the protection of women. That the single sex spaces, uh, for women are that to protect them from men.

And a man who wakes up in the morning and says, actually, I’m a woman, says I can go into a woman’s changing room, should not be allowed to do so. And in my view, most reasonable people think that is the case. You, you, you cannot. Self-identify without going through any procedure or any medical, um, interaction as of an opposite sex and expect to be treated in that way.

And we’ve seen this with, um, sporting activities as well. [00:14:00] And so I think it’s really just common sense. It’s not particularly difficult. And to my mind, this is what most people think. I think this is what my constituents overwhelmingly think. That doesn’t mean that there will be a small number of people as very distinguished historian James Morris, who became Jan Morris, who um, had an operation and so on and so forth, and lived as a woman.

And I think if people go through that full procedure, then it’s a very different situation. I still wouldn’t necessarily say they could compete in female competitions because they have an inherent advantage of the male physique.

Politics in the USA vs. other countriesJohn Anderson: You’ve taken a position that would be not unusual in conservative politics in America in relation to being pro-life, but in your country and in mine and many other Western countries, it’s anathema.

Why is it that [00:15:00] there are such different perspectives in America? You know, it’s a subject of fierce debate, but there’s no debate. It’s a sort of, it’s a dead deal. We’re not gonna reopen it, yawn, go back to sleep. You, you know, you’re just out of order sort of approach, uh, in so many other cultures. How does that, uh, differentiation arise and how do you, how do we understand it?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: It’s, it’s very interesting. I, I wouldn’t necessarily want the UK to have the US politicization of life issues because I think they are above and beyond party politics. Uh, I think politicians have closed it down because it’s too, Awkward, but I think they’re outta touch with voters. Now, I’m not saying that voters take my view because I don’t think they do.

I, I I think they don’t take the teaching of the Catholic church. That’s the starting point on where life begins. But where they do disagree with the consensus, uh, is as far as opinion polling is [00:16:00] concerned. They’re strongly against in the uk sex selective abortions. Yes. Which they think are wrong. They’re increasingly concerned about allowing abortions up to full term for any disability, which is, I think, a terrible thing that happens in this country.

And the bulk of the population are actively against this when asked. And they also would mostly like to see, um, and interestingly, more women than men, a reduction in the number of weeks from 24 weeks down to a lower level. And, and I think politicians. Shy away from it because they think you are either for abortion to full term or you are against it after the moment of conception, which in fact, the bulk of voters in Britain, uh, would like to see greater control, greater safeguards, and, um, the removal of things that are clearly wrong.

I mean, the, the abortion term of [00:17:00] disabled babies is, to my mind so wrong. Uh, we have a society that has become increasingly sympathetic to and helpful to the disabled, but only once they’re born, before they’re born, they are disposable. I just think this is awful, but so do most of the British people.

The current and future state of the Conservative PartyJohn Anderson: I must say that I think one of the most insightful commentators in contemporary Britain, uh, and somebody I must say I’m very fond of personally, uh, is, uh, the amazing Peter Hitchens.

Uh, but he makes a case that the conservative party hasn’t really been conservative for a couple of decades. Yeah. Any comments on that? Uh, how do you feel about his perspectives? Do you share them? Are you optimistic that, uh, in fact, uh, the embers can be stoked back into a fire?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I share your high regard for Pete Hitchens.

I think he’s a very interesting thinker and a good writer and challenges conservatives in an effective, uh, way whilst being broadly on our, our side. [00:18:00] I think the conservative party lost its confidence after Tony Blair won three elections in a row and we came to the conclusion between 2005 and 2010 that the only way to be elected was to be a bit more like new labor.

And we tried that. We then still didn’t win the election, but we have then governed in that way. We certainly, we did in the coalition ’cause we had no choice. The lib downs were there then. We haven’t had much of a majority in 20 until 2019. Then when we got a majority, we were hit by Covid and we’re dealing with Brexit, which was a very conservative thing to do, but was slightly above and beyond conservatism.

So I think there is truth in his analysis and what conservatives need to do is to make the case, we need to make the case for conservatism. Why will this make people better off? Why is it the entrepreneurship Canterbury, who I actually hold in very high regard? I [00:19:00] think he is a genuinely, highly man, was speaking about immigration yesterday and saying that, um, the policy of sending people to Rwanda was immoral.

Now we need to make the case for why conservatism is in fact, moral and good. In my view, sending people to rand is moral and good because it breaks the stranglehold of people, traffickers on an illegal trade that is risking people’s lives coming across the channel. That seems to me a morally good thing to do.

And it requires action to be taken to deter people from coming. And the best way of doing that, that we have been able to come up with is to send them Towanda. And actually, Australia did something similar, uh, and reduced the number of deaths of people trying to get to Australia. That’s true. ’cause you had people coming in, leaky boats and all sorts of terrible things, large numbers of deaths, large numbers of deaths, and those stopped.

Now, surely that is moral and conservatives shouldn’t be frightened of making [00:20:00] the moral case when the left is making the moral case against us.

John Anderson: I think you raised two really interesting points there that I, I feel people on the center and the center right are not as good at as people from the left. The first is make the case build a constituency.

I hear some of those who have followed me saying, John, there’s no constituency for economic reform or for tax reform or for debt reduction. I don’t know if there ever was. You’ve gotta go out and build it. You’ve gotta make the case. And then the second point that I think you raise is that the left is extraordinarily good at prefacing every policy, prescription or pronouncement with a moral statement.

They go to the heart first and then try if they ever do, to reach the head. Whereas center right, people tend to be cold, analytical. This is the way we’ll do it because this is the way to get a sweet set of numbers. We’ve got to, I think if it’s an economic argument, for example, state the moral case, good economics is [00:21:00] good outcomes for people and we’re not very good at it.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Completely agree with you. Um, you have to make the case. It’s very interesting. Um, you all know this better than I do, but I believe not that many years ago, Australia was thinking about introducing identity cards and opinion polls showed something like 80% of people were in favor of identity cards. The case was then made against identity cards.

At which point about 80% of people were against identity cards, and one should make the case and not be too influenced by opinion polls. If I say to you, would you like more taxes to fund the NHS, you’ll all, you probably won’t. But most people say yes, because what’s a good and nice thing to do when I come to you and say, okay, can I have an extra 5% of your income?

You say, no. Why should I give you that? And you’ve got to think through what people mean in opinion polls and whether they’re just saying something that they think sounds good and nice to the person they’re talking to, or whether they [00:22:00] absolutely believe and understand the case. And conservatives need to make the case better, and we need to show that actually our well thought through prescriptions are more caring and better for society as a whole than the Labor party is wearing its heart on its sleeve.

Climate change, green energy, and net-zeroJohn Anderson: I can think of another area where opinion polls say everybody’s demanding action and we’ve got to tackle the problem. It’s called climate change. Then if you turn around and ask how much they’re prepared to pay for it, it turns out to be not very much, I don’t think it’s a very honest debate. I know in my own country it really worries me that, that everyone’s saying we want action.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think we’re responsible 1.1% now in net terms of global emissions, even though we’re a major energy exporter. But everyone wants action. And what worries me is a social impact when people realize how expensive that action is, because they’re not being told. They’re actually being, I think, nothing short of misled when they’re told that the switch to [00:23:00] renewables will reduce power costs.

There’s no evidence of that anywhere in the world for a variety of reasons. You know, renewable energy’s basically only cheap once you put the infrastructure there during the 30% of the time that the wind and the sun blow filling in the gaps makes it a very expensive way to go. And yet there’s no acknowledgement.

There’s no honest dealing with people and I think they just, in the long term, I worry that it just builds more cynicism. Well, I think you’re absolutely right. We had the second reading of an energy bill a couple of days ago in parliament, and this will put huge cost on consumers. This ignores the fact that last September when energy prices went up, nobody was willing to pay them.

But the reason energy prices went up was at least in part because, uh, of the effort to get to net zero. Why do I say that? Well, we haven’t done the things that we would otherwise have done to ensure our own energy supply. We had had something of a moratorium on issuing licenses to drill in the North Sea.

We hadn’t got [00:24:00] on with extracting shale gas. So once you don’t get the basic resource O of fossil fuels, you find you’ve got a shortage. Prices go up. And what happens when prices go up? People say to the government, this is impossible. We must be bailed out. So the government then intervenes. To subsidize the costs that the government itself has created.

And this is absolute madness. And ultimately, Vatas won’t stand for it because governments don’t have any money. So when you get your, um, energy bill and it’s a third of what it might have been because of a government subsidy, that two thirds is still being paid by you, it’s just being paid in taxation rather than, uh, on your energy Bill.

BrexitJohn Anderson: I think I’m correct in saying you are a strong supporter of Brexit. Since then we’ve had covid, we’ve had endless drawn out negotiations and so forth, [00:25:00] and the perception that the British economy is not doing well, that it faces ongoing headwinds, uh, like most Western economies, a lot of unfunded liabilities coming down the road that nobody’s really focusing on.

And I would probably prefer everyone forgot about. You are essentially optimistic, of course. What’s the roadmap for Britain if it’s to recover its prosperity and opportunities for people from where it stands. Now, as you said, it’s a very general question. I know, but you will have thought about it a lot.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: The thing about Brexit is that first and foremost, it’s about democracy. Who should govern us? Should it be the people elected in the UK or should it be unelected people in Brussels? Now, the risk with that is that we might elect worse people than the bureaucrats in Brussels. That’s not impossible.

We might have elected Jeremy Corbin, but we were entitled to do it. And if Jeremy [00:26:00] Corbin had had a mandate, he would’ve been entitled to carry it out. Now, having said that, I have a very clear view of what I think we should be doing economically, but to go back to a earlier point, I have to sell that to the electorate.

So they want to vote conservative to do it. And what is that? Well, it’s free trade. I’m delighted. We, uh, have got a free trade agreement with Australia, which will have a much bigger economic effect than the modelers, uh, predicting that, um, uh, the gravity models of trade, uh, don’t work. They’re outta date, don’t really understand how services work either.

So I think that’s a really positive action. We need more of those and we need to be bold about free trade because actually unilateral free trade makes you more prosperous. Uh, we need to deregulate that the government’s just given up on repealing EU rules. We need to cut through vast s swats of EU rules, say that we can be a more competitive economy because EU regulation is all about creating a protected market for European country [00:27:00] companies within a European sphere.

We want to have an open market that is low cost that people will want to invest in, uh, and will come here to invest in, but also sell their goods into which benefits UK consumers. So it’s about. Open free market, uh, economics, low regulation, and looking globally. And our relationship with Australia’s very important in this, the free trade deal, but also orcas because I think we have a role, uh, as a global strategic player as well as simply a global trading partner.

John Anderson: I was very interested in, uh, just tasing out this issue of why you believe that, uh, the trade agreement between Australia and UK will be of more value, presumably to both economies than people have realized.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Yes, the forecast has been done on the base of gravity models and gravity models are inherently unreliable.

So, economists worked through them on what would happen if the UK joined the Euro and thought it would boost our trade initially by 300%, then revised down [00:28:00] to 200%, uh, with the European Union. Now, there was no evidence for this in the countries that did join the Euro gravity models assume that your trade will be more with the nations to which are closest.

But actually that misses out that so much of trade is now in services which aren’t particularly sensitive to distance, but also that transport costs, shipping costs are relatively low and relatively low proportion of the total cost of sales. So you’ve tended to find, and certainly, um, Australia and the US found that the removal of trade barriers led to much faster increases in trade than were predicted by the models.

The current state of the British EconomyJohn Anderson: Well, that’s good news. Tto return to the broader economic outcome, or outlook for Britain, and this has always been an innovative country. The, if the structures are right, one assumes that Britain’s capacity to reinvent itself [00:29:00] and go forward is sound, but at the moment it looks a bit green. And in particularly, you’ve got a lot of underfunded li liabilities coming towards you, pension schemes and so on and so forth.

How do you see it more broadly?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think you encapsulate it very well that the basic constitutional settlement is sound and it supports the rights of property and freedom of speech. So you, you tend not have a corrupt political, uh, settlement, and that’s pretty fundamental to prosperity in the long run.

But we have put burdens on ourselves that have made us less competitive. So we’ve become the highest tax that we’ve been in 70 years. We’ve adopted EU regulations, which makes us a highly regulated economy. How, how do you deal with that? Well, we have the ability to do that through, um, parliament if we can get conservative messages across and can move to a more efficient, uh, open market.

So that must be the aim, [00:30:00] um, economically for the uk. Can we do that? Uh, yes, I think we can, because as you say, we have the right foundations in place.

Britain's role as the mother-nation of modern freedomsJohn Anderson: We often refer to the British Parliament as the mother of the parliaments. And it’s very easy, I think, to overlook that really modern freedom, modern liberty springs from Britain.

There are people who think that’s an antiquated view or irrelevant or whatever. I don’t think it is at all. It’s not France, it wasn’t the French Revolution, not America in fact, but from Britain. And I just wonder whether younger Britains really understand how important liberty is to a flourishing society and, and maybe the love for liberty is, if you like, being squashed by calls for sustainability, for diversity, for safety, for comfort.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: A little unthinkingly perhaps. I mean, I think you’re right. I think the teaching of history. In schools is not what it was. So people used to be taught the [00:31:00] kings and queens of England, and that was their base for understanding English and then British history. And through that, you understood how our liberties had evolved.

And whether that’s, uh, from Magna Carta in 1215, uh, or it’s the, um, uh, glorious revolution in 1688, or the Great reform bill in 1832. You, you, you saw how liberty was, um, bought effectively, uh, and how power went from the autocratic arms of the state to the democratic arms of the state. And the great thing about the US Constitution is that it is an aim to codify and perfect the British constitution, which the, uh, writers of it greatly admired.

And it’s absolutely fascinating. If you look at the US Bill of Rights, it includes in it the right to bear arms. The right to bear Arms is in the British, the English strictly Bill of Rights. Though oddly ours is the right to bear arms for the maintenance of a Protestant [00:32:00] militia, which as a Catholic, I’m quite glad, has fallen out of fashion.

The US Constitution has, uh, things on acts of attainment won’t happen. Well, acts of attain had actually stopped happening, um, by the 1780s in the UK anyway, but they were trying to stop things that they thought of as abuses and put them in their constitution. So if you look at the history of liberty, I absolutely agree with you.

It emerges from, um, the English political approach, uh, helped by the Scottish, uh, joining in at a, at a later stage. And interestingly, you can trace it back to the Anglos axons that the Normans adopt quite a lot of the Anglos axons institutions with one fundamental principle, which is why it’s not the French fundamental principle of.

English law, and you saw this at the coronation, is that the king is the king under the law. He is not the king above the law. And the [00:33:00] French king was always the king above the law. And the French state after the revolution carried on as if the state was still the royal state. It just didn’t have a king anymore.

On the coronation. And this may be interesting, um, as we share a, a king, um, look what happens doesn’t happen by accident. What is the first thing the king does? The very beginning of it? He takes an oath, then he is acclaimed by the people, then he is anointed by God. Why is the sequencing so important? Well, he’s only anointed by God once he’s been acclaimed by the people, and he’s only acclaimed by the people once he has agreed to rule according to the laws of the land.

William the conqueror did the same. So the whole history of kingship in England is a king who is acclaimed by the people because he’s entered into a [00:34:00] contract. Then God comes along and anoints him or the archbishop, but the the Archbishop acting on behalf of God. And that’s really, really important because the power is a conditional contractual power that the state has.

The MonarchyJohn Anderson: What would you say to people who doubt the value of a monarchy or watch the ceremony wrote as they did in some of our newspapers, that this is weird. Out of touch has no relevance. Has no meaning. Interestingly, they’re people who would never say, would, never would absolutely do you over in Australia. If you criticized Aboriginal rituals, for example, but our own somehow are to be dismissed, you presumably would defend them and point to their values.

What would be your essential argument?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: You’ve always got to be be very careful about ritual because if it becomes ritual for its own sake, it is pointless. It becomes Roan and then people laugh of [00:35:00] it and they don’t take it seriously. The question is, what does the ritual symbolize? And the ritual symbolizes the structure of our constitution and both our constitutions that they are, um, bottom up concepts that lead inevitably to a pinnacle that is the head of state.

Now, whether that head of state is a Monaco, uh, is a governor General doesn’t particularly matter. It matters how you construct your state and what the basis of power is. And the Constitution as a very occasional event, symbolizes that in a way that I think reminds people of how they are in fact governed.

Um, republics do it every four or five years when they, uh, inaugurate a president. There’s much less ceremony involved in that because. You are doing it regularly, and people perhaps think less about the structures of their state in republics, but I think the symbolism illustrates points to, reminds us of [00:36:00] something that is both important and beneficial.

Say it’s not the coaches, I mean, you may like the coaches or you may not like the coaches. They’re, they’re part of the grandeur of it. It’s that actual ceremony that is really very important. Doesn’t exist back, of course, to our history as well. And the stability that our constitution has given us and stability is essential for prosperity.

Unstable states are never prosperous.

John Anderson: I was in America when the Queen became very ill and where I was, it was very, very early in the morning. I’d woken early because my body clock was out because I was in another country. The major programming was all interrupted in America, Republican, Ari America, of course, you know, that broke away from Britain.

Um, the, the news services were saturated with, uh, uh, minute by minute coverage of what was unfolding in Britain. They don’t have a monarchy. They rejected the [00:37:00] model the forefathers argued. You got canceled, if you were an American, founding father who indicated that there might be some value in the British model of monarchy.

And yet here they are having rejected the idea, totally absorbed as I realized, uh, with the idea of the British monarch passing on.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Very interesting. It, it is very interesting and it’s a very British thing because although the Queen was second longest reigning monarch in history, um, she’d only just overtaken the recently deceased king of Thailand, uh, who people hadn’t reacted in this way to.

And when Emperor Hirohito of Japan died after a very long reign, they didn’t react to him in that way either. I think it is the symbolism of monarchy that is so important. And to your point, the monarchy is an indication of liberty that is important. The liberty that the British constitution, the [00:38:00] British model has brought, that’s why it’s interesting, that’s why Americans are interested.

It’s not just the celebrity culture. Um, though I also think that the Queen was a very remarkable woman that, that the role she carried out so well for such a long time was tremendously important over a, a difficult, uncertain period.

John Anderson: A servant model of leadership.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Absolutely.

John Anderson: In an age when we recognize its value. If 4 billion people, I dunno how they measure these things, tapped in to watch it, but it’s not really our value anymore.

Value systems in politics and familiesJohn Anderson: You know, we increasingly teach our children that it’s not about serving others, it’s about you. You’re the center of the universe. When we see that on the stage, when we think our political leaders think it’s about them, not about us, we actually, in a strange way reject the value system we’re instilling in our children, don’t we?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think politicians always have to be very, very careful to remember, uh, that they are there [00:39:00] on behalf of the British people or the Australian people. They’re not there because they themselves are, say marvelous. And I think it’s one of the good things about, um, the FastPass, the post system.

So every weekend I go back to my constituency and almost every weekend I have a surgery where anyone can come and see me and can tell me, um, what I’m doing wrong and what they want me to do better. And I, I have one constituent who was rude to my staff. And so I said to him, you’re not allowed to be rude to my staff, but you are allowed to be rude to me.

I’m your member of parliament. So a few weeks later, he rang up and said, uh, one of my parliamentary assistants, I want to be rude to Jacob. So I took the telephone and he was rude to me. That’s his right, and it’s very important. It’s very direct, and particularly as you go from being a back bench chair to being a minister, it’s easy to get disconnected from your VAs.

And our system of weekly surgeries helps keep our politicians directly linked to remember what they are there to do, [00:40:00] and things like parliamentary privilege. What is my main parliamentary privilege, and I think I say in the house of Commons, cannot be questioned in another court. So I can’t be sued for libel if I say it in the House of Commons.

That’s not a privilege for me because I am, uh, important. It is a privilege for my constituents so I can speak up on their behalf. Likewise, uh, I have a right of unhindered access, phrased as unmolested access, but that gives you the wrong impression to, um, the House of Commons At any time when parliament is, um, in existence, not between the solutions, that’s not there for me, that is there so that I can always get there.

And I can’t have some officials saying to me, where’s your pass? Or, um, you’ve gotta go around that way because I have to be there to represent the interests of my constituents. And it is important to remember the privileges are about your constituency, not about you as an individual. [00:41:00]

John Anderson: I can’t help just, reflecting for a moment. Surgery, as you call it, making yourself available in your office for your constituents. It’s a little easier in a country of this size. My one constituency was the size of your country.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: That is why we’re, it is easier for us and, and for Australians and American politicians. It is obviously much harder because of the numbers or the size or both.

John Anderson: But perhaps your constituents present you with more difficult problems.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I don’t know about that.

COVID and libertyJohn Anderson: COVID, you know, uh, we all now I think, look back and certainly in my country with some concern about how we handled it. You’ve expressed some strong views. I think, such eminent people as, Lord Jonathan Sum, have expressed the same views. I think they, to my way of thinking, they go to the heart.

A little bit of the idea of who owns our liberties. Are they somehow the gift of government or are they ours? That we [00:42:00] surrender only to the extent that we need to for the common good. And shouldn’t we be more recognizing of the fact that it’s not for governments to gift us. Freedoms. It is for them to defend them sometimes against their own interests and desires, but it’s their job to defend them and to recognize that they, it’s in the same theme as you’re talking about serving the electorate, serving the people rather than lauding it over them.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I was in government at the time, so I was barred by collective responsibility. Um, and I was reading Jonathan Sum and was thinking, good heavens, this man is talking sense. Um, that, that, uh, I, I know him anyway, but then I’ve always thought extraordinarily highly of him and what he was saying just seemed to me to be right.

The answer that I’m unfortunately was given regularly in government circles was that lockdowns were polling very well. People wanted to be told what to do, and frankly, that’s not good enough that people [00:43:00] have rights over their own lives, and where I think we got it wrong, And I think Australia got it more wrong than we did actually.

Was that after the first lockdown, which was legitimate because we didn’t know. We were in the dark at that point in time and it could have been much worse than it was by the second lockdown. We knew it wasn’t actually that dangerous. And we also knew that people were broadly pretty sensible, that people were inevitably flexing the rules.

But inevitably, as a politician, I was being as careful as I possibly could be. I assumed there was a photographer from a left wing newspaper in the garden on basis if you assumed that you’d probably behave well, uh, or at least within the rules. But I think lots of my constituents allowed the rules to be uh, um, not looked at too carefully once we got in second and subsequent lockdowns.

And the government should have reacted to that rather than thinking it could force people to do things. I hope. [00:44:00] And I think this is potentially very good news, that if any government ever tried this again, nobody would take any notice. I think the government exceeded its ability to tell people what to do, and by the end of it, people had enough, and subsequently they realized it was nonsense anyway.

So you take all this mask wearing that we had to do, which I didn’t like doing. I didn’t maintain the right of members of parliament, not have to wear masks on the grounds of our unhindered access. You, you cannot create a new rule for member of parliament without primary legislation, however trivial it may seem.

Um, but now people know wearing masks didn’t do any good or anybody else any good. Why would you wear a mask again? So I, I, I think people wouldn’t put up with it, uh, on another occasion.

John Anderson: So perhaps there’s some good that can come out of this. It might check governments in the future. Jacob, you allude to the way Australia’s perceived on the international stage.

There’s, there’s. I actually participated in a television program in [00:45:00] America, two hours. Whatever has happened to the Australians that they allowed themselves to be so tied down and lent on, particularly in the state of Victoria, Melbourne.

The Chinese Communist PartyJohn Anderson: It is a widely held perception, though I, I would hope on the other side, which is to raise a new topic, uh, that we might be seen as having been quite plucky and to have stood for our own interests when it comes to the way that the Chinese Communist party’s been behaving.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well, I’m very pleased to come onto that. Um, uh, happy to answer. I was astonished by Australia of all countries. Um, with lots of space being as, uh, locked down as it was, uh, and then finding it very difficult to get outta lockdown and the Australian people putting up with it, it it, but then nobody expected.

I, I sat in on meetings at the beginning of lockdown where the experts said to us, well, you will have [00:46:00] lockdown fatigue and we must bring in lockdown late because if we bring it in too early, you’ll have lockdown fatigue and people won’t be taking any notice of it when you really, really need it. That turned out not to be true, that people were happy to be locked down for months and months.

Um, but on China, I cannot tell you how much I admire the courage of Australia to its own economic risk of standing up to a totalitarian regime and leading the western world that, that the western world, the US and the uk. We’re going along with this, um, golden age view of China that we could deal with them ignoring every human rights abuse that was going on in China, the treatment of the Uyghurs, and then the treatment of Hong Kong.

And just thinking this could all go along swimmingly. And it was Australia that stood up and said, no, this is not right. Um, we are gonna do something about it. You had trade [00:47:00] sanctions then slapped on you, you didn’t back down. I think you then sold your iron all to other countries for just as good prices.

So the economic effect was not as bad as expected. And then the US and the UK changed. And I, I think this is really important actually in terms of, um, there’s an awful word, geopolitics, but I can’t think of a better one, because it shows what an important free mid-sized country can do to change the view of the Western world for the better and for the stronger to stand up for our shared values.

John Anderson: I would give quite a bit of credit to Japan as well. And they’ve got some baggage in this area, to be honest, from the 1930s and 40s. But nonetheless, they have made it very plain that, they will do their bit. And I think that is an emboldening between the two countries. It’s emboldening the region to say, well, we don’t have to sacrifice our freedoms [00:48:00] and our opportunities to, a very authoritarian regime. Always important to distinguish between the Chinese people and the regime.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Yes. I mean, it is a totalitarian, communist regime. And that is not the fault of the Chinese people. They never get a chance to vote for it. But you are right about Japan, and you are right about how Japan has been trying to handle this as tactfully.

As possible with the difficult history. It’s very important. There was an agreement between Japan and South Korea very recently. Yes. And that is, uh, um, I, I used to be an, an emerging markets investor, um, and also included Asia. So I used to go to South Korea quite often. And the, um, view of Japan, because of the war and ’cause of colonialism is not enormously positive.

So that Japan [00:49:00] and South Korea are cooperating is I think a really important step forward.

John Anderson: I’d be very interested in your views on, on, on the geopolitical outlook. Firstly, Orca, who plainly troubles Beijing Deeply, which tells you that I think maybe they’re worried by the coming together. It really reflects what’s happened in relation to the Ukraine.

The West is not quite as decadent. As degenerate and divided as they thought, and they’re prepared to stand by their values. That’s encouraging. How do you see orcas when you’ve talked about the trade relationship between Australia and Britain, but orcas is a very new development that will have major implications beyond the geopolitical, I think in binding a mid-level country, Australia, uh, with Britain and America.

I’d be very interested in your thoughts on it.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think it’s really very important. [00:50:00] I think it’s from British point of view, a benefit of Brexit. We could not have done it if we were in the European Union and bound by the doctrine of sincere cooperation with the eus foreign policy, which would’ve overridden orus.

And as you remember, the French were very angry about AUKUS and we would’ve found it impossible to do. I think it is a reflection of actually two mid-size countries, Australia and the UK being in able to influence. The progress of the West, because for the US to have done it on its own would’ve been impractical. It needed partners and it needed in a way validating because I think the US after Iraq and Afghanistan has become quite sensitive about its international involvement for which it gets very little thanks and a great deal of criticism and therefore to do something with two willing partners of a smaller size who were willing to take a lot of the publicity around.

It was, I think, [00:51:00] helpful to bring the US out of the renewed isolation that the withdrawal from Afghanistan had created and the humiliation of the withdrawal from Afghanistan as well. So I think it was important in so many ways, important for the UK reestablishing itself as. Um, globally interested, important for Australia and seeing benefits of what it had done previously in standing up to China and getting Western support and important for the US and allowing it slightly to come out of its shell.

It’s really, really fundamental importance when I’d like to see the UK go further. Australia’s involved in the, in the quad with Japan and India and the US as well. I’d like to see us join that because I think that is the root to global security.

The Russia-Ukraine conflictJohn Anderson: These are dangerous times. I can’t not ask you your views on Ukraine and, I might preface, the request that you tell us what you think by saying that I look on and worry about how it might end.

[00:52:00] I worry about the extraordinary commitment by the Americans, the potential for it to impact in various ways, um, economically, uh, the supply of limited weaponry. Enthusiasm for, you know, engagement internationally at a time when we would like their focus to be very clearly, frankly, on the Pacific region.

And we wonder, we see Britain doing a lot of heavy lifting. We wonder a bit about Europe, and I particularly think perhaps the French and the Germans could do a bit more so that the Americans weren’t quite so heavily burdened here at a time of great danger elsewhere.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think the greatest danger in the Pacific would’ve been if we’d done nothing in Ukraine, because it would’ve shown that the international Order had broken down, that it was a free for all.

And what would’ve stopped China invading Taiwan overnight whenever they felt like it. So I, [00:53:00] I wouldn’t worry that you are less secure because of the US commitment to Ukraine, and you are absolutely right, but I should always think what is the exit. But there are some times when you have to enter, even if you don’t know what the exit is.

Uh, this was very definitely one of those times because I agree with that. If Putin had succeeded again after annexing the crime era, um, about 10 years ago, where would you have stopped? And this is so Redot, actually it was the Prince Wales. There was the king who pointed this out when Crimea was invaded.

He got a lot of stick for it. He said, this is redolent of the 1930s when Germany invaded bits and pieces for more living space. The arguments were so sinisterly similar that Putin was using and that he went back for more. Not expecting the West to say no. The West did say no, and this has [00:54:00] stopped him. He is not now going to invade Atonia or Poland, uh, or any of the other neighboring countries.

And this has massively increased our global security. It has also, uh, been very helpful in terms of persuading China of the limits of what it can do. That doesn’t mean we should ignore China because China has been building up alliances in the Middle East. It’s got Saudi Arabia talking to Iran. We should be very concerned about that.

We should be very concerned about the way our relationships in the Middle East are deteriorating and actually the US Biden has been, not good in our relationship with Saudi Arabia.

John Anderson: The irony is that for all of the criticism, Trump actually was far more effective in the Middle East. I. I think than the current President.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Trump was amazingly effective in the Middle East. I saw, in the UK, uh, the ambassador from the u a e and he said to me, was I [00:55:00] aware that it was easier for somebody from u a E to get into Israel than to get into the United Kingdom because of our visa and passport control. And that was Trump. That was Trump who brought them together and he deserves a lot of credit for that.

USA's future involvement on the global stageJohn Anderson: We’ve got, you know, obviously, an approaching presidential election in America and what happens there is very important to the rest of us. I sometimes wonder whether the election of our prime minister in Australia is as important as who the Americans elected as their president. Uh, it’s not an insignificant matter.

The issue that I’d be interested in your views on is that we are picking up. And you’ve already alluded to this, a certain weariness in America about global involvement. They get very little thanks for it. We expect them to be there whenever there’s a problem, and then we criticize ’em uphill and downhill all the time.

You can, I don’t blame them for sometimes thinking, why do we bother, to be honest, but we can’t afford that attitude. I worry, [00:56:00] I wonder whether it worries you that the next presidential campaign in America may very well feed isolationist views, which would be worrying in the context of an uncertain globe.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: It is always a feature of American politics and it’s particularly always a feature, uh, of Congress, isn’t it? That most senators and, uh, most, um, members, house of Representatives are interested quite rightly in their constituents and don’t like foreign engagements, and that’s been true for a long time. So it’s presidents who have to lead the way in foreign policy, and presidents have considerable leeway in what they can do of the US Constitution.

But Donald Trump, when he was President, wanted a realignment. I mean, he wanted to go back to your question on Ukraine, uh, Germany and France to pay more for the defense of Europe. Not entirely unreasonable thing to ask for. Uh, it is, it is difficult. [00:57:00] We needing American engagement. Um, and we have to be very careful that there is a tendency for, um, non-American journals to be very dismissive and politicians of American political figures who may then be leaders of the free world.

We have to be quite careful about what we say, even if what goes on in American politics is very surprising from a UK or an Australian perspective.

Growing disengagement in politics among youthJohn Anderson: I’d be very interested in just, uh, teeing out some of, um, uh, your own, uh, Views on a couple of matters. Lord Sum in one of these consultations, talked about this being the age of disengagement and he talked about the staggering fall off in the number of card carrying members of the major political parties, for example.

And that’s certainly true in my country as well. At every level you hear at school boards can’t get, people who are prepared to go on the sporting clubs have trouble. The local shows can’t find young people [00:58:00] coming through. Um, uh, and right up to the top level. The political party find sometimes now, uh, that, uh, there are very few people who want to take the job on.

Uh, when I left and it was a safe seat, uh, there were only three people when I’d run 20 years before that there were 12 who wanted the job, the job. When, when John Howard had first run p sleep, there were 33 candidates. The age of non, non, non-engagement. Do you see that as a, as a, as a, a, how do we counter that?

How do we get people saying, I want to contribute. I need to contribute. There’s something I can do and it, I should do it.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: It’s really interesting how things have changed. Um, why does anybody take on any voluntary trusteeship? Because if you were asked 20 years ago, somebody would say to you, John, will you be a trustee of this body?

But usually I’m delighted. That’s fine. Now what will they say? They’ll say, will you apply and send in a CV and be interviewed by a couple of teenagers [00:59:00] to see whether you are suitable to, um, go onto this body? Uh, then will you do some course on diversity and inclusion to see if you are suitable for it?

And by the way, here are all the liabilities that you take on by joining this body. And people think, well, no, no, I’m doing this as a favor. I’m not doing this ’cause I need it as a CV point. I’m doing it because this body needs somebody. I, I’m, why does anyone take on being chairman of the B B C in the UK anymore?

Most of them end up being forced out, having to retire for one reason or another. They get no political support when they get into difficulties. Uh, they get paid very little for it compared to jobs of similar size in the private sector. Um, and their reputations get trashed by the end of it. Why would anyone do that?

And so you, you’ve got a, a sort of societal pressure against engagement. Why didn’t people join political parties? I suppose they’ve got other things to do. I mean, they’re more various [01:00:00] forms of entertainment. Um, I’m perhaps more worried about participation in elections. How do we keep vote, uh, voter numbers up?

I know you have compulsory voters. Yes, which I’m not in favor of. I think it is a freedom not to vote as much as it’s a freedom to vote. That I think is easier. I think people vote when it matters. So in the Scottish independence referendum, you had the highest voting level since the 1950s in the. Uh, Brexit referendum, you had the highest voting level since the 1990s.

When people think it matters, they will turn out to bait and that’s for politicians to make happen. But with the more general engagement, I think you’ve just got to make things easy for people. Again, um, David Cameron had this thing about the big society, which I quite liked as an idea. The problem was it had to be new.

Whereas what I wanted was those people who were doing coronation street parties, just to be able to do them rather than have to register with the council, tell the police they were closing the roads, [01:01:00] put the advert up. If on the name of the coronation you had the odd raid through a village was closed, did that really matter? Could we just be a bit more flexible?

What drives Jacob Rees-Mogg forward in politicsJohn Anderson: A bit lighter touch, but you’ve stepped up out of conviction, whatever the obstacles, and sometimes in the face of hostility to your views, you have stepped up to your great credit. What drives you?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Oh, well, I think politics is extraordinarily interesting and I think that the country can be better government and I think I have something that I can contribute to that.

I think conservative ideas work. We need people who believe in them and are willing to, um, articulate them and put them as powerfully as they can, but I confess I enjoyed doing it as well. Uh, and um, when, when people say to me, well, what about the intrusion and this and that and the next thing, and Twitter not always being, uh, entirely, um, atory, um, I point out that I chose to do it and I didn’t have to choose to do it.

John Anderson: You are well known as a man of, of [01:02:00] strong Catholic convictions. You will have been subjected, uh, I can take this for granted. Uh, I was, uh, uh, to this sort of line that you should leave your religious views behind when you enter the cabinet room as though anybody can leave their worldview behind. But that has not, uh, discouraged you from being very open and very honest about your views.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: No, I, I mean, religion is not party political in this country when, not like America, that, um, uh, America in this extraordinary position that if you’re a Republican, uh, you, um, have to be anti-abortion and pro capital punishment. Uh, I’m anti both. Uh, and I, I, I think it’s, it’s fascinating how, um, US politics has created this, uh, um, bifurcation.

Um, but I think that the issues of life are of extraordinary importance. It worries me, [01:03:00] saddens me that we live in a culture of death and that is death of the newborn and its death of the ill, uh, with euthanasia being increasingly, I. Um, common in civilized countries. Uh, and I think this is wrong. It’s not a party political matter, but I think it’s really important to speak out about it. I think it’s wrong for moral reasons, but I also think it’s wrong for practical reasons too.

Moral RelativismJohn Anderson: On the issue of ethics, you’ve commented, I think that there’s a problem with moral relativism and indeed, I think more broadly there’s a problem, if I can put it this way, that if there’s no authority over government, if there’s no God that there’s no absolute rights and wrong, then government becomes God and principle is thrown out the door and everything becomes about power.

But can you just elaborate on what you mean when you say there are issues and [01:04:00] shortcomings in the concept of moral relativism?

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: I think your point on power is absolutely heart of it. In the Westminster system, parliament can legislate on absolutely anything that it wishes to legislate on. But that doesn’t mean that all its legislation will be legitimate.

It it, and this is actually the argument that Henry iii, um, found him himself in with Thomas Moore. Thomas Moore was saying that there is a natural law and the parliament cannot override this natural law. And I think that must be true, that there must be limits even to what a democratic parliament can, uh, vote for it.

It can’t abolish the family, for example, even though the state has always been in competition with the family because the family is a power block, the greatest power block against the state. It’s why the state, uh, is to some extent jealous of the family. So I think there are overriding principles. That, um, you can’t change by statute [01:05:00] law, moral relativism.

I mean, I suppose the problem is it’s all relative to what you mean, isn’t it? That’s what you’re trying to get at with moral relativism and there are no absolutes, are there no fundamentals. And I think there are some fundamentals, and I think one of them is life.

ConclusionJohn Anderson: I admire your courage and I know that I’m not alone in that. And you’ve been very generous with your time.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Well you’re very kind, I have very little courage. It, it’s very easy in UK politics saying what you think, uh, if you are on the right. The people who have the real courage are people like the lady who ran for the leadership of the SNP who won a party of the left.

Expressed similar views, um, because she was absolutely pillared for that. And it was thought that somebody of her views could not stand for a quote, a progressive party. [01:06:00] Now on the right, there is much more tolerance that the, the right in modern times is the party of tolerance, whereas the left has become intolerant.

John Anderson: Extraordinary, really? That, isn’t it? There’s a lot of truth to the old saying that, the right thinks the left is misguided, and the left thinks that the right is evil.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: Yeah. I’m afraid that’s true.

John Anderson: Yeah. Well, again, thank you so very much.

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg: It’s absolute pleasure. I’m, I’m sorry I had to go the house of comments midway through the interview and come back again.